Dismantling the CoVID gap

Nothing has been normal since the pandemic hit schools last spring. The current back-to-school climate has produced an unprecedented anxiety in all educational stakeholders, returning our gaze to how CoVID is further exacerbating the ‘achievement gap’ between well-resourced and the working class families. While wealthier families mobilize into learning pods, some of us continue the fight to keep marginalized groups at the center of the conversation. At Language Matters, we believe Language Learners (LLs) matter, especially during the changing winds of pandemic schooling decision-making. Within this context, the rhetoric on LLs’ are (predictably) framed in the same deficit narrative. Now we face the “CoVID gap” or “CoVID Slide” which does little to actually redress our focus on the resources LLs bring to their schooling or the rich array of learning experiences that occurs outside the traditional classroom space. This post aims to educate teachers of LLs about deficit Discourses around LLs in an effort to inspire a more positive view of their learning as we (re)enter distance learning this fall.

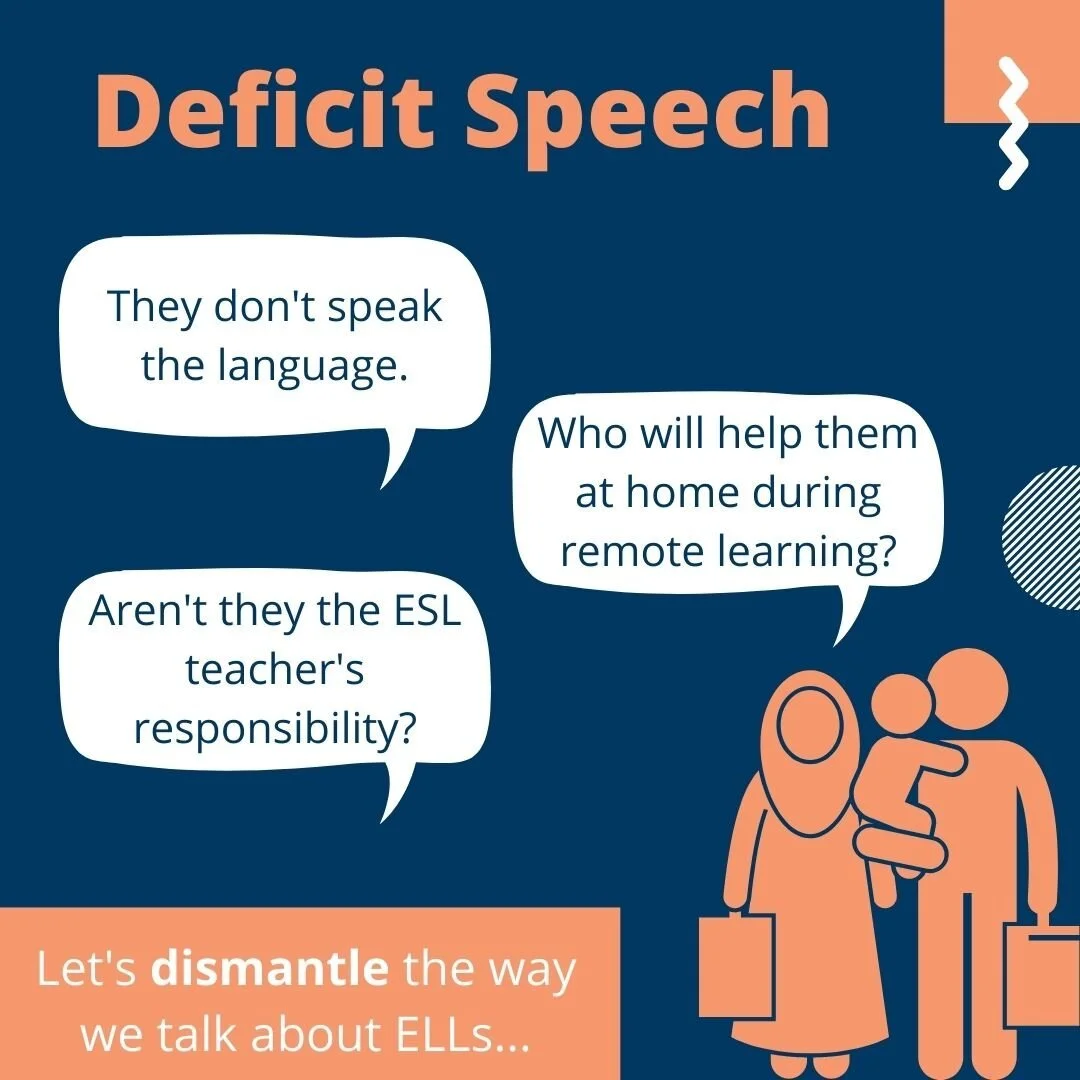

The typical story about LLs positions them as inherently deficient in language abilities, which makes them unlikely to succeed in American schooling.

There is a long, politically contentious history that positions LLs in US public education in a deficit or remedial perspective. Ann Hass Dyson offers a helpful description of a deficit view of language: “[when] the intersection of socially and politically influenced attitudes and opinions about language [mix] with attitudes and opinions about groups of people.” In this history, there emerges a “typical story” that positions immigrant and second or third generation learners as inherently deficient in language abilities and, therefore, unlikely to achieve academic success in this country. Consider the evolution of labels we’ve assigned to these students: from Limited English Proficient (negative) to English Language Learner (neutral) to Emergent Bilingual (empowerment). Let’s take a moment to problematize the central metaphor of an “achievement gap” that connotes a race with winners and losers, a race with benchmarks normed against a white, middle-class ontology. The framing is so baked-into our thinking of bilingual kids, they didn’t have a fighting chance to be viewed otherwise when schools went online. That’s precisely what this writer at Ed Week decided in his blog post about LLs at the start of the pandemic: the verdict was out about their “falling behind” before remote learning even began.

The Discourses we consume about a population of learner matters because we unintentionally begin to think in similar ways. These ideas seep into our consciousness, even when we dedicate ourselves to supporting LLs in our classrooms! That’s why I put together the following list of statements about LLs. I offer you some redirected solutions to begin dismantling the deficit language in your thoughts, often with an eye towards the assets our learners bring to their schooling.

With a mindshift in place to renew our commitment for LLs to thrive in a remote-learning classroom, let’s advance our project to honor and leverage the resources they bring to their learning. Immigrant families have a baked-in culture of resilience to not only survive but thrive in their communities. Theirs is a language of resilience and creativity in the face of adversity, marshalling cultural, linguistic and working-class values that are invisible in the mainstream curriculum. Take Luis Moll and colleagues who theorized about Latinx families’ funds of knowledge, or the home- and community-level industries (e.g.: cooking, budgeting, child-care, gardening etc..) that help make a household run smoothly. We have Guadalupe Valdes to thank for her ethnography of Latinx youth as language-brokers for their first-generation parents. These “special cases of gifted-and-talented” youth provide impromptu translations for government, health care and schooling endeavors, ensuring their families are active participants in American society. There’s the notion of a hybrid or ‘third space’ learning context that blends community and school knowledge to exciting new frontiers (h/t Kris Gutierrez). To extend the discussion towards a proper dismantling framework, Django Paris and Sammy Alim want to disrupt the business-as-usual values in public education, asking us to consider:

“What if the goal of teaching and learning with youth of color was not ultimately to see how closely students could perform White middle-class norms but to explore, honor, extend, and, at times, problematize their heritage and community practices?”

Will Language Learners be left behind this year? Let’s hope that’s not the question your principal asks of you when you open your laptop on September 1st. Let’s readdress the real challenge in schooling: the pervasive framing of LLs as remedial, language-less and lacking support. Oftentimes the re-frame can happen internally and on your own, try using the “instead of… consider this” chart listed above. And if all else fails and you still feel overwhelmed to support your LLs this fall, Language Matters is only an email away to help you bring an empowerment framework to your virtual classroom.